Death in Sicily - macabre, violent and beautiful

Stone cross in the Santo Spirito cemetary in Palermo.

Detail of marble tomb (anno 1697) in the floor in the Church of San Pancrazio, Taormina. Saint Pancras (aka Pancratius / San Pancrazio) is the patron saint of Taormina.

A tombstone in four languages. Sicily, AD 1149. This funerary inscription was set up by Grisandus, a Christian priest, for his mother Anna in AD 1149. Her eulogy is written in Judaeo-Arabic (Arabic written in Hebrew script) on top, Latin on the left, Greek on the right, and Arabic below.

Death is always considered the end of everything, a very sad moment for all the people who loved the deceased. Here we are going to look at how Sicilian men and artists have dealt with death through time.

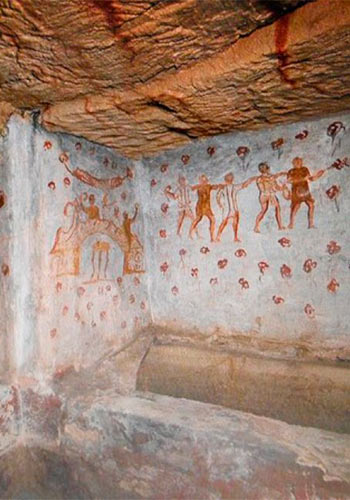

In the III century, people used to create and decorate underground tunnels (better known as catacombs, even if the correct name is “ipogeo (English: Hypogeum or hypogaeum (plural hypogea) – from the ancient Greek, hypo (under) and gaia (mother earth or goddess of earth), meaning: underground) to celebrate the new life of the soul of the dead.

Inside the ipogeo of Crispia Salvia in Marsala (near Trapani), you can recognize the dead sitting on a chair while is playing a flute. In front of her there are five men dancing and a banquet called refrigerium.

The refrigerium was a real practice made in honor of the dead; people used to eat and drink all together near the grave of their beloved one. It symbolizes the contact with God and the Holy Communion with bread and wine.

Stylized flowers scattered all over the wall are symbol of Paradise: a beautiful garden full of roses and plants! There is also a peacock with its colored tail, symbol of the resurrection.

Still nowadays people in Sicily are used to visit the dead’s house bringing food and beverages. It’s a way to communicate their respect and closeness.

During the Middle Age a brand new way to express devotion and pain spread, closer to people’s everyday lives.

“Death is real, people shouldn’t be afraid of it, it’s not the end but a new life in the arms of God!” – this is what the Church said.

That’s why in the XV century popular institutions, such as hospitals or orphanages, start to call artists to create frescos and paintings about death and life! Images were the only way to transmit ideals, especially in places where people were unable to read.

The Triumph of Death

The Triumph of Death. Fresco in the Regional Gallery of Palazzo Abatellis in Palermo.

This wonderful fresco is saved in the Museum of Palace Abatellis in Palermo. It’s the most representative work of "international" Gothic Art in Sicily. Like an illuminated manuscript, this work of art is painted with extreme precision and softness.

All the attention is captured by the Death who’s riding a skeletal horse while launching arrows against people belonging to different social levels.

We don’t know the name of the artist who painted it, maybe it belongs to Tommaso De Vigilia, but due to the loss of the majority of his works it’s impossible to confirm it. In origin this fresco was located in the Hospital of Palace Sclafani, Palermo, and it was used to convince sick people to accept their fate of death.

Palazzo Sclafani, situated near the Palermo cathedral and the Palazzo dei Normanni. Constructed in 1330 by lord Matteo Sclafani, Count of Adernò.

La Festa dei Morti ("Feast of the Dead")

On All Souls' Day (2 November) La Festa dei Morti ("Feast of the Dead") is celebrated in Sicily! In the night between November 1 and 2, the deads visit their alive beloved ones bringing gifts to the children. These gifts are hidden in the house and found in the early morning (a sort of treasure hunt). In addition to toys, kids can find also sweets, such as the special typical biscuits of this party: the tarall donuts with sugar ice, the Tetù or Tatù biscuits white and brown, dried fruits and chocolates, martoran fruits and "u' Pupi ì zuccaru" a sugar puppet painted like a medieval knight. The day continues with a visit to the cemetery where their closest and dearest dead are resting.

Memento mori

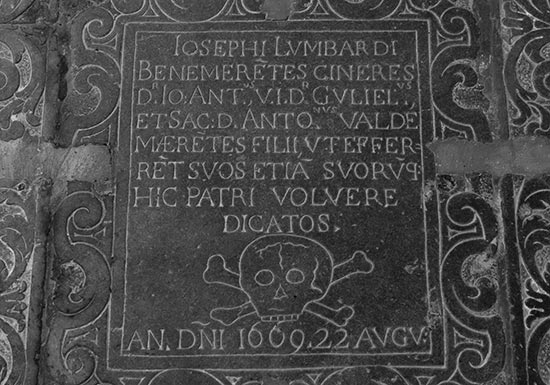

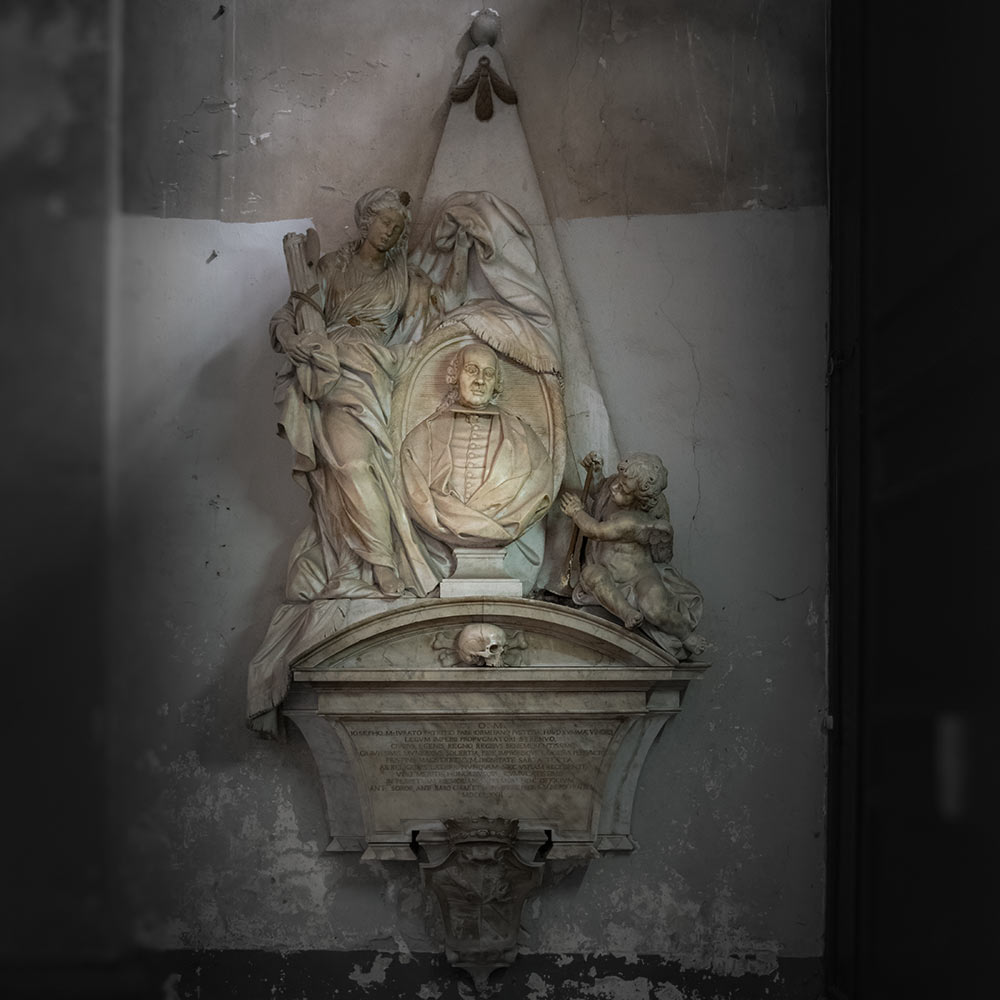

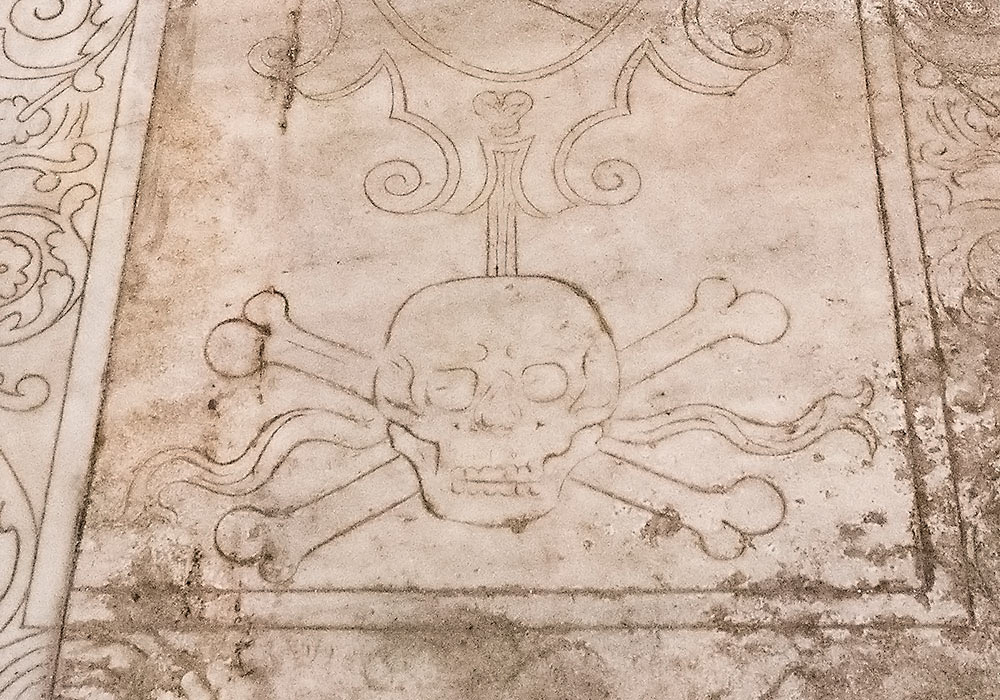

From XVII to XVIII Century the idea of “memento mori” (Latin - remember, you’ll die) develops and spreads in a lot of sculptures and graves inside churches , with the symbol of a skull.

Church of the Purgatory, Ragusa Ibla.

Church of the Purgatory, Ragusa Ibla

Tomb (1772) in Chiesa di S. Ninfa dei Crociferi, Palermo.

Stucco by Giacomo Serpotta in Chiesa di Sant'Orsola, Palermo.

The floor of the church San Giorgio dei Genovesi in Palermo is covered with marble tomb-slabs dating from the 17th and 18th centuries.

Detail of a marble tomb-slab in the church San Giorgio dei Genovesi in Palermo. There was no date on this grave, but it was probably made in the second half of the 17th century.

Memento mori. Decoration over the entrance of Chiesa della Maddalena (church of Santa Maria Maddalena), Ragusa, first built in the seventeenth century and later re-built (18th century).

Another important idea close to the “memento mori” and the skull was the idea of “Vanitas” (Latin - vanity): the inevitability of death and the transience of earthly achievements and pleasures.

St. Hilarion in the arms of Death

This canvas of Agostino Scilla is saved inside the deposit of the Regional Museum of Messina. It represents an unusual scene, absolutely legendary, of St. Hilarion in the arms of Death.

The life of Saint Hilarion of Gaza (291-372 AD ) was transmitted mainly orally. He renounced his inheritance after the death of his parents and he distributed all his richness to the poor people.

At first glance the image results very disturbing and dark; however, the scene is set in the quiet solitude of a natural promontory under the shade of a tall oak tree with the trunk divided into two, symbol of strength of mind but also symbol of the dualism life – death.

The saint appears deeply immersed in a sleep, a sort of a loss of consciousness. Ecstasy and death tend to merge and coincide in the unique experience of ecstasy of the holy penitent. He knows and accepts peacefullly the end of his life while the Death came to take him. He gently covers his chest with his own hand, he’s ready to go.

The celebration of death is divided between earthly and spiritual.

While poor people, saints and martyrs wanted peace and memory, Kings, Queens and noble people wanted the eternal glory.

The results were incredible shows all around the city at the sunlight and unexpected choices.

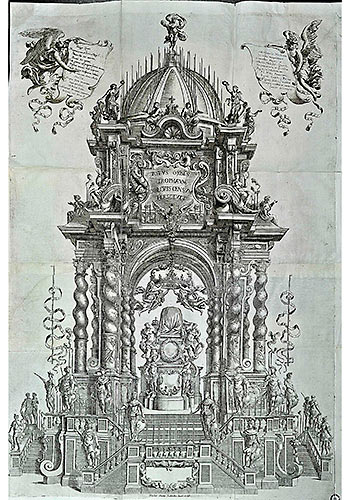

The print is taken by the volum “Le solennità lugubri e liete in nome della Sicilia nella città di Palermo celebrate per la morte del re cattolico Filippo IV e per le acclamazioni di Carlo II figlio ed erede “ 1666, and it represents the grave of Philip IV of Spain, King of Sicily, decorated with a spectacular Baroque construction. The style is characterised by its use of exaggerated motion in order to produce drama and meraviglia (Italian - wonder).

This one represents the funeral of Queen Maria Luisa of Bourbone. The great procession, after being in the Cathedral and passing through the city, reaches the Royal Palace waiting for the last farewell. A great parade of musicians, nobles, representatives of the clergy and poor people, all together for the loss of the Queen of the Empire.

Catacombs of the Cappuccini

While the Kings and Queens spent lot of time preparing funeral processions in front of millions of people, noble people just wanted to rest immortal underground. A lot of noble people were "buried" in the Catacombs of the Cappuccini with generous donations. In the early XVII century, in fact, the Cappuccini community, during an excavation to enlarge the mass grave behind the main altar, discovered forty-five friars naturally mummified and incredibly preserved by the time and the decomposition.

One of the mummies in the Catacombs of the Cappuccini, Palermo.

Catacombs of the Cappuccini

Rich people wanted to remain in their status of dignity and power, so mummification became a status symbol, a possibility for the families of the deceased to see and venerate the body of their relatives in a not ordinary way.

This trend was interrupted in 1880, except for more two bodies: the body of Giovanni Paterniti, Vice-Consul of the United States in 1911, and the body of the little Rosalia Lombardo, who died at the age of two years in 1920, famous all around the world.

Today the practice is more symbolic and less spectacular. People visit the house of the deceased for two-three days, then the grave is conducted inside the church for the blessing with a little procession in the middle of the street , where everything is stopped and unknown people make the holy sign of the cross as a symbol of respect and blessing.

Rosalia Lombardo

The entrance to the catacombs in Palermo.

Photo: Per-Erik Skramstad / Wonders of Sicily

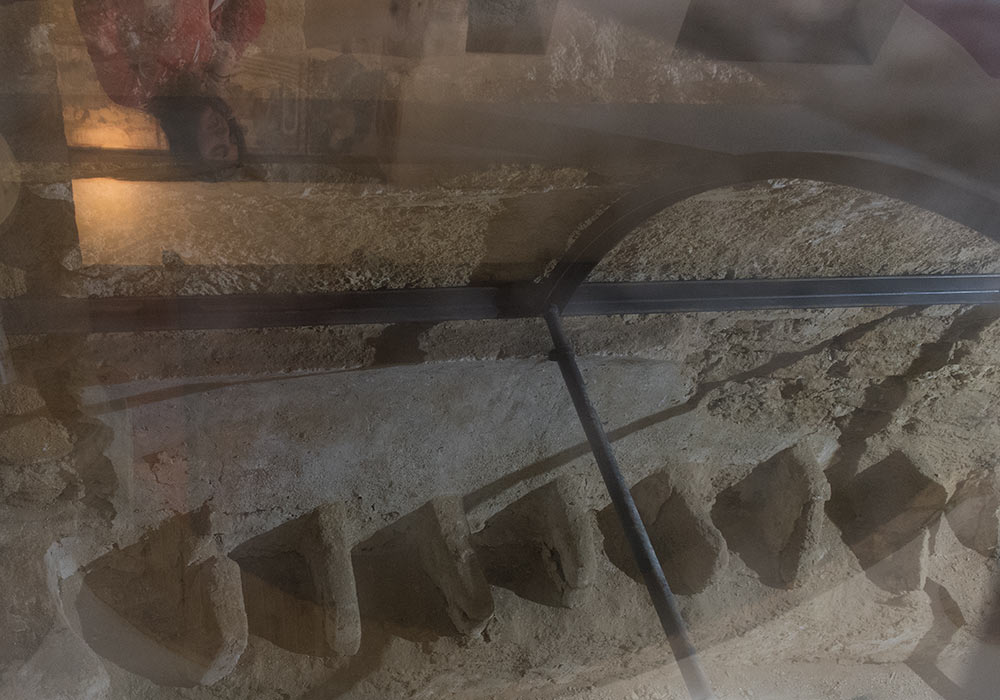

Through the floor in the church Santa Maria dei Greci, Agrigento, you can see a 15th century Capuchin crypt used for mummification (the bodies were placed upright in the seats, and the fluids drained into the hole in the centre of the room)

Death in Cefalù. A grave in the local cemetery.

Announcing the death of a beloved one (Ragusa): The Italians post notices (so called manifesti funebri) announcing deaths and funerals. In Sicily, death is something horrible for the family so everyone has to know their pain and join it. It is a kind of respect for the dead and the family.

Memorial stone in Cefalù.

Tomb at the Cefalù cemetery.

Memorial

Memorial dedicated to Sicilians who lost their lives during World War II

To the Sicilians who fell for freedom

ANPI FIAP FVL

1943-1945

ANPI, FIAP, FVL are acronyms of organizations tied to the Italian resistance movement during World War II:

ANPI: Associazione Nazionale Partigiani d'Italia (National Association of Italian Partisans), an organization of Italian WWII partisans and resistance fighters.

FIAP: Federazione Italiana Associazioni Partigiane (Italian Federation of Partisan Associations), another group promoting the legacy of resistance.

FVL: Federazione Volontari della Libertà (Federation of Freedom Volunteers), a group commemorating those who voluntarily fought for freedom.

The years 1943-1945 signify the timeframe when Italy was deeply involved in World War II and its internal struggle against Fascism and Nazi occupation, particularly after the fall of Mussolini.

Relics

Crucifix in Oratorio del SS. Rosario di San Domenico, Palermo. Behind the glass are human bones. The Oratorio is more known for the marvellous stucco decorations by Giacomo Serpotta.

Detail of an altarpiece in Chiesa di Sant'Orsola, Palermo.

Human remains behind glass in Chiesa di San Francesco, Agrigento.

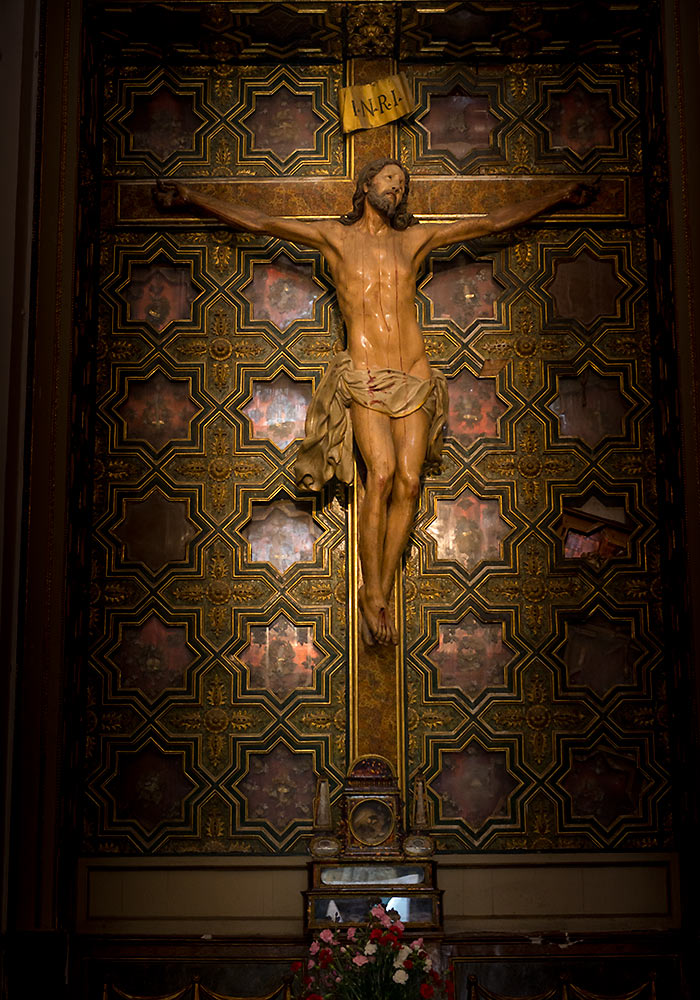

Crucifix in Basilica dell'Immacolata (Chiesa di San Francesco), Agrigento.

Crucifix in the church of the Purgatorio (San Lorenzo), Agrigento. Behind the glass you see relics.

Chiesa dell'Anime del Purgatorio (Church of the Souls of Purgatory), Caccamo.

Detail of the exterior of the Church of the Purgatorio (Santo Stefano Promartire) in Cefalù.

Detail of the exterior of the Church of the Purgatorio (Santo Stefano Promartire) in Cefalù.

Monument in the cemetary in Cefalù, Sicily.

Detail of a iron cross in the cemetary in Cefalù.

.

Tomb from Carini, 28 kilometers from Palermo. It has two cells and dates back to 3000 BC. It is now in the courtyard of the Archeological Museum in Palermo (Museo Archeologico).

Sarcophagus for the nobleman Francesco Perdicaro (died in 1567) in the Norman church La Magione, Palermo.

Arcosolium in the Valley of the Temples, Agrigento

The cliff-line of the Valley of the Temples, Agrigento, served as a natural defensive wall during the Greek period. The cavities in this "wall" (arcosolia, singular: arcosolium) characterized by an a curved upper surface are tombs made between the 4th and the 7th century AD.

Byzantine tomb-recesses, Via Pirandello

Byzantine tomb-recesses in the wall. Via Pirandello, Taormina, a couple of hundred metres from Grand Hotel Miramare.

- Death in Sicily

- Arcosolium, Valley of the Temples, Agrigento

- Byzantine tomb-recesses in the wall on Via Pirandello, Taormina

Tomb in the Church of San Pancrazio, Taormina. "Pregate per me povero peccatore" (Pray for me poor sinner).

The Tomb of the Norman King William II of Sicily in the Monreale Cathedral.

Sarcophagus of Cecilia Aprile (dead 1495), made by the workshop of Francesco Laurana (1430-1502). It was once located in Chiesa di Sant’Agostino, Palermo, now in Galleria Regionale, Palazzo Abatellis.

Thanks to Laura Leonardi!

Opening hours of the crypt of the Chiesa Madre in Gangi