Siracusa (Syracuse)

Siracusa, a historic city on the island of Sicily, is renowned for its rich Greek and Roman heritage, including ancient amphitheaters and architecture. Founded by Greek settlers from Corinth and Tenea, Siracusa became a powerful city-state, allied with Sparta and Corinth, and was a key player in Magna Graecia. In the 5th century BC, it rivaled Athens in size and influence, with Cicero calling it "the greatest Greek city and the most beautiful."

Later, Siracusa became part of the Roman Republic and Byzantine Empire, briefly serving as the Byzantine capital under Emperor Constans II. Though eventually surpassed by Palermo, it remained significant through Sicily’s history. Today, Siracusa is a UNESCO World Heritage Site, with a population of about 125,000. It is also mentioned in the Bible for Paul’s visit, and its patron saint is Saint Lucy, celebrated on December 13.

The baroque cathedral in Siracusa.

The Temple of Apollo is one of the first things you see when you are entering the island Ortigia, which is joined to the mainland by three bridges.

Siracusa (en. Syracuse) - a historic city, the capital of the province of Syracuse. Together with seven other cities in the Val di Noto, Siracusa is listed among the UNESCO World Heritage Sites.

The Magnificent Cathedral (Duomo) in Siracusa

Detail of the decorative ornaments of the baroque cathedral in Siracusa.

The facade of the Cathedral in Syracuse, a powerful Sicilian-Baroque composition erected in 1728-54. It was designed by Andrea Palma.

New and old: Spiderman and the cathedral in Syracuse behind him.

Santa Lucia

The statue of Santa Lucia (Saint Lucy). Saint Lucia was born around 286 (or 283?) in Siracusa, Sicily. She is a historical figure who undoubtedly suffered martyrdom in Siracusa, likely around 304 during the persecutions under Emperor Diocletian (284-305). Her memory was honored early on, with a Greek inscription in the Giovanni Catacomb in Siracusa from around 400 mentioning that a girl named Euskia died on Lucia's feast day. The inscription was discovered in 1894 along with her burial site, Loculus. Lucia is also mentioned in the canon of the Mass and is one of the most highly revered Christian virgin martyrs.

The Legend of Santa Lucia

Lucia was born in Siracusa to wealthy parents of high social status. Her Roman father died young, leaving her Greek mother, Eutychia, to raise her. From an early age, Lucia vowed to remain chaste and give her wealth to the poor, though she kept this secret. When her mother arranged a marriage to a pagan nobleman, Lucia prayed to be saved from it.

Eutychia suffered from an incurable illness, and Lucia persuaded her to visit Saint Agatha’s tomb in Catánia. During prayer, Agatha appeared to Lucia, saying her faith had healed her mother. In gratitude, Eutychia allowed Lucia to remain unmarried and donate her dowry to the poor.

Angered by this, her rejected fiancé reported her as a Christian to the Roman governor, Paschasius, during Emperor Diocletian’s persecution in 303. Lucia was arrested and tortured but remained steadfast in her faith. Attempts to defile her by sending her to a brothel and to burn her failed, as she could not be moved or harmed.

Finally, Lucia was sentenced to death by the sword. Before dying, she predicted the end of Christian persecution, the fall of Emperor Diocletian, and the death of his co-regent, Maximian. Lucia received the sacraments before passing away, becoming one of Christianity’s most revered virgin martyrs.

Lucia’s name, which evokes the idea of light (Latin: lux), may have been the reason she became the patron saint of eyesight, leading to people commonly invoking her for eye ailments. However, legends often offer more dramatic explanations, and in art, she is frequently depicted holding a plate with two eyes on it.

Lucia’s legend likely dates back to the 5th century. While its details are uncertain, there is no doubt about the great honor she received in the early Church. She is one of the few female saints mentioned in Pope Gregory the Great’s (590–604) Canon and appears in his Sacramentarium and Antifonarium. Lucia is also included in the earliest Martyrologium Romanum, and her name appears in Greek liturgical books, the marble calendar in Naples, and the martyrology of Saint Jerome from the 6th century.

Lucia’s tomb in the Lucia Catacomb in Siracusa was rediscovered in the 6th century, and a Byzantine-style octagonal chapel was built over it. Though it has been rebuilt several times, it still stands today. In the 12th century, it was expanded into the Basilica of Santa Lucia. Notably, the basilica houses a granite column where she was allegedly executed, and a masterpiece by Caravaggio, The Burial of Saint Lucia (1609), adorns the church.

The fate of Lucia’s relics is debated. According to monk Sigebert of Gembloux (1030–1112), her body remained in Sicily for 400 years before being transferred to Corfinium, Italy. Emperor Otto I then moved it to Metz in France in 972. From there, an arm was sent to a monastery in Speyer, Germany. However, in Siracusa, a rib of Lucia is still preserved, while other relics were taken to Constantinople in 1038 by the Byzantines. After the city’s capture in 1204, the Venetians brought some of her relics to Venice, where they are now enshrined in the church of Santi Geremia e Lucia. Her skull was reportedly given to King Louis XII of France in 1513 and placed in Bourges Cathedral. Lucia is commemorated on December 13 in both the Western and Eastern Churches. Her feast day, celebrated as a festival of light in the darkest month of the year, is particularly popular in Italy, Sweden, and across Scandinavia, as well as in parts of Europe like Hungary, Serbia, and Croatia. In Sweden, the tradition dates back to at least 1780. Before the Gregorian calendar reform, Lucia’s night was considered the longest of the year.

The song Santa Lucia remains popular in Sicily and Scandinavia, and her feast is marked on Norway’s ancient calendar, the primstav. Lucia is one of seven female saints named in the Roman Canon, alongside Agatha, Cecilia, and others.

Her main attributes in art are a palm branch, a lamp, and two eyes on a plate.

Artemide fountain.

Photo: Mark Elderton

Baroque balconies in Syracuse.

Photo: Mark Elderton

The portal of the Norman church remain intact.

A boy playing melodies from The Godfather near the church Santa Lucia alla Badia (La chiesa di Santa Lucia alla Badia) on the south side of Piazza Duomo. Is it the missing Holy Grail he is collecting his money in?

Lucia’s tomb in the Lucia Catacomb in Siracusa was rediscovered in the 6th century, and a Byzantine-style octagonal chapel was built over it. Though it has been rebuilt several times, it still stands today. In the 12th century, it was expanded into the Basilica of Santa Lucia. Notably, the basilica houses a granite column where she was allegedly executed, and a masterpiece by Caravaggio, The Burial of Saint Lucia (1609), adorns the church.

The church of Santa Lucia alla Badia (La chiesa di Santa Lucia alla Badia) is located on the south side of Piazza Duomo. The Bavarian-baroque facade from 1695 is made by Luciano Caracciolo.

Detail of the ornaments above the entrance of Santa Lucia alla Badia (La chiesa di Santa Lucia alla Badia), Syracuse.

Photo: Per-Erik Skramstad / Wonders of Sicily

Photo: Mark Elderton

Photo: Mark Elderton

Coins

Description: Sicily, Syracuse AV Dilitron. Emergency issue of the Second Democracy, winter 406/5 BC. Obverse die signed by 'IM...'. Head of Athena left, wearing crested Attic helmet decorated with serpent, palmette and elaborate spiral tendrils, [ΣΥΡΑΚΟΣΙΩΝ before, IM below truncation of neck] / Aegis with gorgoneion at centre. Boehringer, Essays Thompson, pl. 38, 12 = Hess Leu Sale (27 March 1956), lot 210 (same obverse die); Manhattan Sale I, 28 (same dies). 1.76g, 10mm, 7h. Near Mint State. Extremely Rare; one of very few known specimens - only one other on CoinArchives. Ex Roma Numismatics XI, 7 April 2016, lot 114.

The year 406 marked a desperate time for the Greeks in Sicily. A great Carthaginian invasion of Sicily had commenced in the Spring to punish the Greeks for having raided the Punic territories of Motya and Panormos. 60,000 soldiers under Hannibal Mago in 1,000 transports along with 120 triremes sailed for Sicily, where despite a plague that ravaged the ranks of the Carthaginian army and felled its commander, they successfully besieged and sacked Akragas, the wealthiest of all the cities of Sicily. After razing the city to the ground, the Carthaginians under their new commander Himilco marched east to Gela. Despite a spirited defence of the city by the defenders and the arrival of a relief force of 34,000 men and 50 triremes under Dionysios of Syracuse, the city fell after a poorly coordinated and unsuccessful attack launched by the Greeks. As Dionysios retreated from Gela first to Kamarina and then back to Syracuse, both of these now indefensible cities were sacked and levelled by Himilco's forces. It was against this backdrop of a desperate fight for survival that many emergency coinages were issued in Sicily. Gold was scarce in the Greek world and tended to be used only for emergency coinages, as in that famous instance when Athens in the last decade of the fifth century resorted to melting the gold from the statues of Nike on the Akropolis when cut off from their silver mines at Laurion. Gela, Akragas, Kamarina and Syracuse all issued emergency gold coinage in 406/5 BC, without doubt to pay the mercenaries they had hired in their doomed resistance to Himilco. The master engraver 'IM...' responsible for this coin is also known to have engraved Syracusan tetradrachms around this period (see Tudeer 67). Thanks a lot to Roma Numismatics!

Description: Sicily, Syracuse AR Tetradrachm. Deinomenid Tyranny. Time of Hieron I, circa 480/78-475 BC. Charioteer driving walking quadriga right, holding kentron and reins; Nike above, flying right, crowning horses / Head of Arethusa right, wearing earring and necklace, hair tied with pearl headband; ΣVRΑΚΟΣΙΟΝ and four dolphins around. Boehringer 330 (V163/R229). 16.83g, 24mm, 11h. Good. Very Fine. Thanks a lot to Roma Numismatics!

Coin from Selinunte (Museo Mandralisca, Cefalù)

Photo: Wonders of Sicily

The Archeological Park

The Greek theatre in the Archeological Park, one of the most celebrated of all the ruins of Siracusa. With its 138 metre in diameter, it is the largest Greek theatre in Sicily. To the right you see preparations for the evening's performance of Verdi's Aida.

- See more photos of the Archeological Park in Syracuse here!

The Roman amphitheatre in Syracuse (140m by 119m). It was used for gladiator fights. The rectangular depression was probably for the machinery used in the spectacles.

- See more photos of the Roman amphitheatre in Syracuse here!

Fonte Aretusa

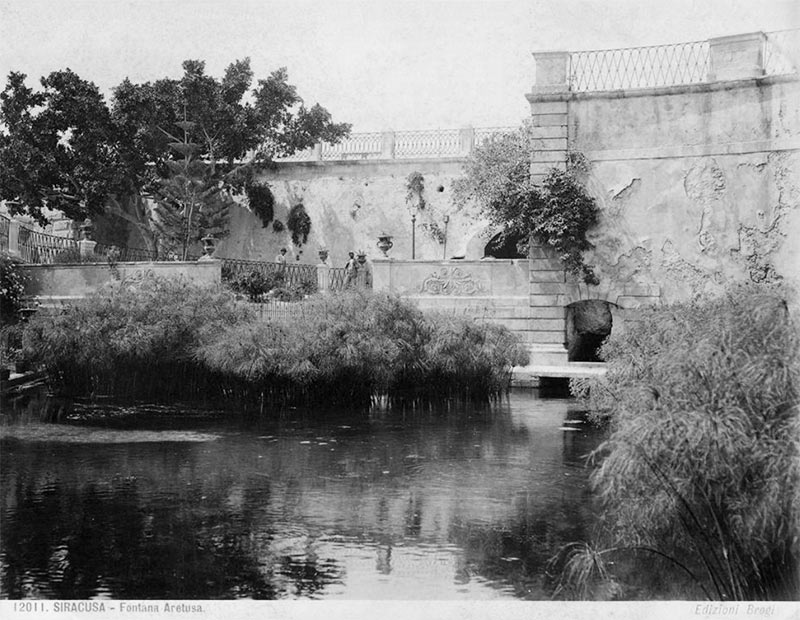

Fonte Aretusa, one of the most famous fresh-water sources of the Greek world. The pond was built in 1843.

Photo: Per-Erik Skramstad / Wonders of Sicily

The story of Arethusa (Ovid: The Metamorphoses V:572-641

Calliope sings: Arethusa’s story “Ceres, kindly now, happy in the return of her daughter, asks what the cause of your flight was, Arethusa, and why you are now a sacred fountain. The waters fall silent while their goddess lifts her head from the deep pool, and wringing the water from her sea-green tresses, she tells of the former love of that river of Elis. ‘I was one of the nymphs, that lived in Achaia,’ she said ‘none of them keener to travel the woodland, none of them keener to set out the nets. But, though I never sought fame for my beauty, though I was wiry, my name was, the beautiful. Nor did my looks, praised too often, give me delight. I blushed like a simpleton at the gifts of my body, those things that other girls used to rejoice in. I thought it was sinful to please. Tired (I remember), I was returning, from the Stymphalian woods. It was hot, and my efforts had doubled the heat. I came to a river, without a ripple, hurrying on without a murmur, clear to its bed, in whose depths you could count every pebble: you would scarce think it moving. Silvery willows and poplars, fed by the waters, gave a natural shade to the sloping banks. Approaching I dipped my toes in, then as far as my knees, and not content with that I undressed, and draped my light clothes on a hanging willow, and plunged, naked, into the stream. While I gathered the water to me and splashed, gliding around in a thousand ways, and stretching out my arms to shake the water from them, I thought I heard a murmur under the surface, and, in fear, I leapt for the nearest bank of the flood. ‘What are you rushing for, Arethusa?’ Alpheus called from the waves. ‘Why are you rushing?’ He called again to me, in a strident voice. Just as I was, I fled, without my clothes (I had left my clothes on the other bank): so much the more fiercely he pursued and burned, and being naked, I seemed readier for him. So I ran, and so he wildly followed, as doves fly from a hawk on flickering wings, as a hawk is used to chasing frightened doves. Even beyond Orchemenus, I still ran, by Psophis, and Cyllene, and the ridges of Maenalus, by chill Erymanthus, Elis, he no quicker than I. But I could not stay the course, being unequal in strength: he was fitted for unremitting effort. Still, across the plains, over tree-covered mountains, through rocks and crags, and where there was no path, I ran. The sun was at my back. I saw a long shadow stretching before my feet, unless it was my fear that saw it, but certainly I feared the sound of feet, and the deep breaths from his mouth stirred the ribbons in my hair. Weary with the effort to escape him, I cried out ‘Help me: I will be taken. Diana, help the one who bore your weapons for you, whom you often gave your bow to carry, and your quiver with all its arrows!’ The goddess was moved, and raising an impenetrable cloud, threw it over me. The river-god circled the concealing fog, and in ignorance searched about the hollow mist. Twice, without understanding, he rounded the place, where the goddess had concealed me, and twice called out ‘Arethusa, O Arethusa!’ What wretched feelings were mine, then? Perhaps those the lamb has when it hears the wolves, howling round the high fold, or the hare, that, hidden in the briars, sees the dogs hostile muzzles, and does not dare to make a movement of its body? He did not go far: he could see no signs of my tracks further on: he observed the cloud and the place. Cold sweat poured down my imprisoned limbs, and dark drops trickled from my whole body. Wherever I moved my foot, a pool gathered, and moisture dripped from my hair, and faster than I can now tell the tale I turned to liquid. And indeed the river-god saw his love in the water, and putting off the shape of a man he had assumed, he changed back to his own watery form, and mingled with mine. The Delian goddess split the earth, and plunging down into secret caverns, I was brought here to Ortygia, dear to me, because it has the same name as my goddess, the ancient name, for Delos, where she was born, and this was the first place to receive me, into the clear air.’ ” (Translated by A. S. Kline © 2000 All Rights Reserved This work may be freely reproduced, stored, and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose.)

Fontana Aretusa, Siracusa. Photo by Carlo Brogi (1850-1925)

Giorgio Locatelli's soft spot for Sicily

The Italian chef Giorgio Locatelli tells of his soft spot for Sicily: "The island has so many magical places: the ancient amphitheatres of Syracuse; the little town of Erice, where there are more churches than houses; the Norman cathedral of Monreale. The Villa Romana del Casale, just outside the town of Piazza Armerina, has an incredible collection of Roman mosaics. They include beautiful mosaics of girls in bikinis. Romans! In bikinis! My kids thought that was so funny; they loved it."

Read more in The Guardian

The distance between Siracusa and some other cities in Sicily

Siracusa-Agrigento 217 km

Siracusa-Catania 66 km

Siracusa-Cefalù 249 km

Siracusa-Modica 72 km

Siracusa-Noto 38 km

Siracusa-Palermo 277 km

Siracusa-Ragusa 90 km

Siracusa-Taormina 118 km

Siracusa-Trapani 375 km

Kayak Polo (also known as Canoe Polo) in Syracuse.

Kayak Polo (also known as Canoe Polo) in Syracuse.

And finally an espresso.

Photo: Torild Egge

Winston Churchill visits Syracuse in 1955

Sir Winston Churchill On Holiday (1955)

Silver tetradrachm coin, Siracusa, about 470 BC. British Museum.

Photo: Per-Erik Skramstad / Wonders of Sicily

Sicily: Some geographical names in Italian, Sicilian, English, Latin, Arabic and Greek

- Agrigento (Sicilian: Girgenti, Ancient Greek: Akragas (Ἀκράγας), Latin: Agrigentum, Arabic: Kirkent or Jirjent)

- Agrigentum, Latin for Agrigento

- Akragas (Ἀκράγας), Ancient Greek for Agrigento

- Àsaru, Sicilian for Assoro

- Assorus, Latin for Assoro

- Assoros, Greek for Assoro

- Baarìa, Sicilian for Bagheria (also the title of a film by Giuseppe Tornatore)

- Balad al-fīl ("the Village (or Country) of the Elephant"), one of the Arabic names for Catania

- Balarm, Arabic for Palermo

- Butirah, Arabic for Butera (one of the largest cities in Arab Sicily)

- Càccamu Sicilian for Caccamo

- Castrogiovanni (until 1926 Enna was known as Castrogiovanni)

- Castrugiuvanni, Sicilian for Enna

- Cefalù (Sicilian: Cifalù, Greek: Κεφαλοίδιον, Diod., Strabo, or Κεφαλοιδὶς, Ptol.; Latin: Cephaloedium, or Cephaloedis)

- Cephaloedium or Cephaloedis, Latin for Cefalù

- Cifalù, Sicilian for Cefalù

- Egesta, Greek for Segesta

- Enna (Sicilian: Castrugiuvanni; Greek: Ἔννα; Latin: Henna and less frequently Haenna). Until 1926 the town was known as Castrogiovanni.

- Gibilmanna: The name 'Gibilmanna' derives from Arabic 'gebel / jebel' (mountain) and 'manna' (edible substance extracted from the manna ash trees).

- Girgenti, Sicilian for Agrigento

- Henna / Haenna, Latin for Enna

- Hyspicae Fundus, Latin for Ispica

- Ispica (Sicilian: Spaccafurnu, Latin: Hyspicae Fundus)

- Jirjent, Arabic for Agrigento (also: Kirkent)

- Kefaloidion or Kefaloidis (Κεφαλοίδιον / Κεφαλοιδὶς), Greek for Cefalù

- Kentoripa, ancient Greek for Centuripe

- Kirkent, Arabic for Agrigento (also: Jirjent)

- Madīnat al-fīl ("the City of the Elephant"), one of the Arabic names for Catania

- Noto (Sicilian: Notu; Latin: Netum)

- Notu, Sicilian for Noto

- Netum, Latin for Noto

- Palermo (Sicilian: Palermu, Latin: Panormus, from Greek: Πάνορμος, Panormos, Arabic: Balarm, Phoenician: Ziz)

- Palermu, Sicilian for Palermo

- Panormos (Πάνορμος), Greek for Palermo

- Panormus, Latin for Palermo (from Greek: Πάνορμος, Panormos)

- Qaṭāniyyah, allegedly from the Arabic word for the "leguminous plants"

- Sarausa, Sicilian for Siracusa

- Selinous, Greek for Selinunte

- Selinus, Latin for Selinunte

- Siggésta, Sicilian for Segesta

- Siracusa (English: Syracuse, Latin: Syracusæ, Ancient Greek: Syrakousai (Συράκουσαι), Medieval Greek: Συρακοῦσαι, Sicilian: Sarausa)

- Spaccafurnu, Sicilian for Ispica

- Syracuse, English for Siracusa

- Syracusæ, Latin for Siracusa

- Syrakousai (Συράκουσαι), Ancient Greek for Siracusa

- Syrakousai (Συρακοῦσαι), Medieval Greek for Siracusa

- Taormina (Sicilian: Taurmina, Greek: Ταυρομένιον Tauromenion, Latin: Tauromenium)

- Taurmina, Sicilian for Taormina

- Tauromenion (Ταυρομένιον), Greek for Taormina

- Tauromenium, Latin for Taormina

- Terranova is the old name for Gela (the fifth largest town in Sicily)

- Ziz, Phoenician for Palermo