Serpotta Stuccoes in the Oratorio del Santissimo Rosario in Santa Cita, Palermo

Donald Garstang argues that the elaborate details, dramatic events, opulent decorations, and rich materials used in the celebration of religious holidays in Palermitan churches significantly influenced Giacomo Serpotta. He believes this influence is particularly evident in the Oratorio del Santissimo Rosario in Santa Cita.

In 1685 Serpotta began to decorate the oratory.

The confraternity Compagnia del SS. Rosario in S. Cita was founded in 1570 by Father Maiano Lo Vecchio to take part in the annual processions in honour of the Madonna of the Rosary. The building of the present Oratory was probably finished around 1680, but Donald Garstang suggests in his monumental work Giacomo Serpotta and the Stuccatori of Palermo 1560–1790 that building must have been protracted over most the seventeenth century.

Stylistic differences between the various parts led some scholars to believe that many of the stuccoes were not made by Serpotta, but when finally Monsignor Meli was admitted to the archive, he found that the decoration indeed was by Serpotta but executed at different times; actually thirty years separated the work in the nave from that in the chancel.

Serpotta started working on the stuccoes in 1685. In 1707-08 Serpotta was paid for 'constatura di stucco', which Garstang believes means restoration, repair or the last touches diven to a decoration. In 1707 Michele Rosciano was paid for having guilded the devices of the allegorical figures.

In 1695 Maratti's painting The Madonna of the Rosary was sent from Rome.

The small oval cupola was frescoed with The Coronation of the Virgin by Vincenzo Bongiovanni in 1719.

Source: Donald Garstang: Giacomo Serpotta and the Stuccatori of Palermo 1560-1790

Serpotta putto in Oratorio del Rosario di Santa Cita, Palermo.

Timeline of the Oratorio del Santissimo Rosario in Santa Cita

1570

The Compagnia del SS. Rosario in S. Cita was founded in 1570 by Father Mariano Lo Vecchio

1680

The building of the present Oratory was probably finished around 1680.

1685

Serpotta begins to decorate the Oratory.

1688

The stuccoes of the nave were for the most part finished.

1695

In 1695 Maratti's painting The Madonna of the Rosary was sent from Rome.

1717

Serpotta begins to decorate the chancel.

1719

The small oval cupola was frescoed with The Coronation of the Virgin by Vincenzo Bongiovanni in 1719.

The Battle of Lepanto (7 October 1571). A fleet of the Holy League, a coalition of European Catholic maritime states arranged by Pope Pius V, inflicted a major defeat on the fleet of the Ottoman Empire in the Gulf of Patras. In the history of naval warfare, Lepanto marks the last major engagement in the Western world to be fought entirely or almost entirely between rowing vessels, the galleys and galeasses which were still the direct descendants of the ancient trireme warships. The battle was in essence an "infantry battle on floating platforms". It was the largest naval battle in Western history since classical antiquity, involving more than 400 warships. The victory of the Holy League is of great importance in the history of Europe and of the Ottoman Empire, marking the turning-point of Ottoman military expansion into the Mediterranean. It was also of great symbolic importance in a period when Europe was torn by its own wars of religion following the Protestant Reformation, strengthening the position of Philip II of Spain as the "Most Catholic King" and defender of Christendom against Muslim incursion. (Wikipedia)

The Confraternities

Confraternities are voluntary associations of laypeople, predominantly within the Roman Catholic tradition, established to promote works of charity or piety under the authority of the Church. The term “confraternity” derives from the Latin “frater,” meaning brother, and typically refers to lay organizations not centered on occupational roles. These associations often operate under the oversight of a bishop and within the framework of canon law. Confraternities predominantly consist of male members.

Historically, confraternities have varied in composition, including clerical, lay, or mixed memberships. Lay confraternities, in particular, were commonly composed of aristocrats or merchants who possessed the financial resources to support charitable endeavors. These activities often focused on assisting disadvantaged groups within their communities, although some confraternities were established primarily for the benefit of their members. Additionally, certain confraternities were linked to influential patrons, further enhancing their capacity to undertake philanthropic or religious missions.

Charitable work was a central feature of confraternities. Activities ranged from providing medical aid and burying the dead to offering dowries for impoverished girls and caring for the sick. In some cities confraternities of penitents performed acts of charity combined with penitential practices such as fasting, wearing hair shirts, and other forms of self-discipline. These groups were often distinguished by the colors of their processional robes, such as white, black, blue, and red, each color associated with specific activities.

An important sub-classification of confraternities includes those centered on penitential acts.

The arts also played a significant role in the activities of confraternities. Artistic endeavors reflect the deep integration of visual, musical, and architectural elements into the religious and social missions of confraternities.

The structure and activities of confraternities highlight their role in preserving the patrimonial traditions of Catholicism, particularly in shaping women's roles and experiences within the Church.

The Oxford English Dictionary defines confraternity as “a brotherhood; an association of men united for some purpose or in some common profession; esp, a brotherhood devoted to some particular religious or charitable service.”

Processions are of great importance for many Sicilian confraternities.

Giacomo Serpotta (10 March 1652 – 27 February 1732): Child with helmet in a anti-war stucco detail in Oratorio del Rosario di Santa Cita.

Stucco sculpture of a child holding their hands to their chest, symbolizing vulnerability and a sense of self-protection.

Saint Zita of Lucca (~1218–1278)

Feast Day: April 27

Patron Saint of Lucca; maids, housekeepers, and servants

Saint Zita (Citha, Cita, Scytha, Sitha) was born around 1218 in Monsagrati near Lucca, Italy. Her name means ‘girl’ and lives on in its diminutive form, zittella, meaning "unmarried woman" in Italian. She was the daughter of Giovanni and Bonissima Lombardo. Her family was devout.

Due to her family's poverty, Zita received little formal education. Even as a child, she lived a deeply spiritual life guided by simple principles. Whatever she did, she would first ask herself, “Will Jesus like this?” With this question in mind, she grew into a devout and industrious girl, helping on her parents' farm and selling their produce at the Lucca market.

At the age of 12, Zita entered service in the household of Pagano di Fatinelli, a wealthy weaver and silk merchant in Lucca, 12 kilometers from her home. She remained there for the next 48 years of her life. Zita was pious and conscientious in her work. With her mistress’s permission, she rose very early each day, attending Mass at San Frediano church before beginning her duties, which she carried out with unmatched diligence. This devotion initially caused resentment among the other servants, particularly as Zita also declined invitations to indulge in leisure or revelry. Yet, she maintained her cheerful disposition and treated everyone with kindness.

Zita was kown for her care for the poor. She often gave away her own food and clothing. She often offered her bed to beggars, sleeping on the floor herself. Her patience and goodness eventually won the respect and friendship of both the family and her fellow servants.

In her later years, Zita was relieved of many household duties to focus on caring for the sick and poor, as well as ministering to prisoners condemned to death. Stories of miracles and supernatural visions began to surround her. One tale recounts that angels baked bread in her stead while she was in a rapturous state. Another story tells of her secretly giving away beans from the household stores during a famine, only to find the remaining beans miraculously multiplied when her master inspected the pantry.

A particularly famous story highlights Zita’s generosity. On Christmas Eve, her employer, seeing her inadequately dressed for the cold, lent her his fur coat, insisting she return with it. On her way to church, Zita encountered a beggar shivering in rags and, moved by compassion, gave him the coat. After Mass, she found the beggar gone and returned home deeply distressed. However, the next day, a stranger arrived with the coat, leading people to believe the beggar was an angel in disguise.

Zita passed away in Lucca on April 27, 1278, at the age of 60. She was buried in San Frediano, the Romanesque church of the Canons Regular in the old town of Lucca. Zita’s tomb was opened in 1446, 1581, and 1652, and her body was found to be incorrupt. Today, she rests in a glass coffin in the Cappella di Santa Zita, dressed in the garb of a servant. After her death, she was venerated as a saint by the people.

A biography written in Latin by Fatinello degli Fatinelli in 1372 marked the beginning of her canonization process. Both Dante (in Inferno, XI, 38) and Fazio degli Uberti referred to Lucca simply as "Santa Zita." Her cult was approved by Pope Leo X in the early 1500s for San Frediano church. In 1696, Pope Innocent XII formally canonized her by confirming her cult, and in 1748, Pope Benedict XIV included her in the Roman Martyrology.

Zita’s feast day is celebrated on April 27. She is the patron saint of Lucca and household workers, and her image appears in the city’s coat of arms. In 1931, Pope Pius XI declared her the primary patron of maids and domestic servants.

She is often depicted in work attire, holding a purse and keys, or bread and a rosary.

More photos

Decorative detail in Chancel. It was made c 1685–88.

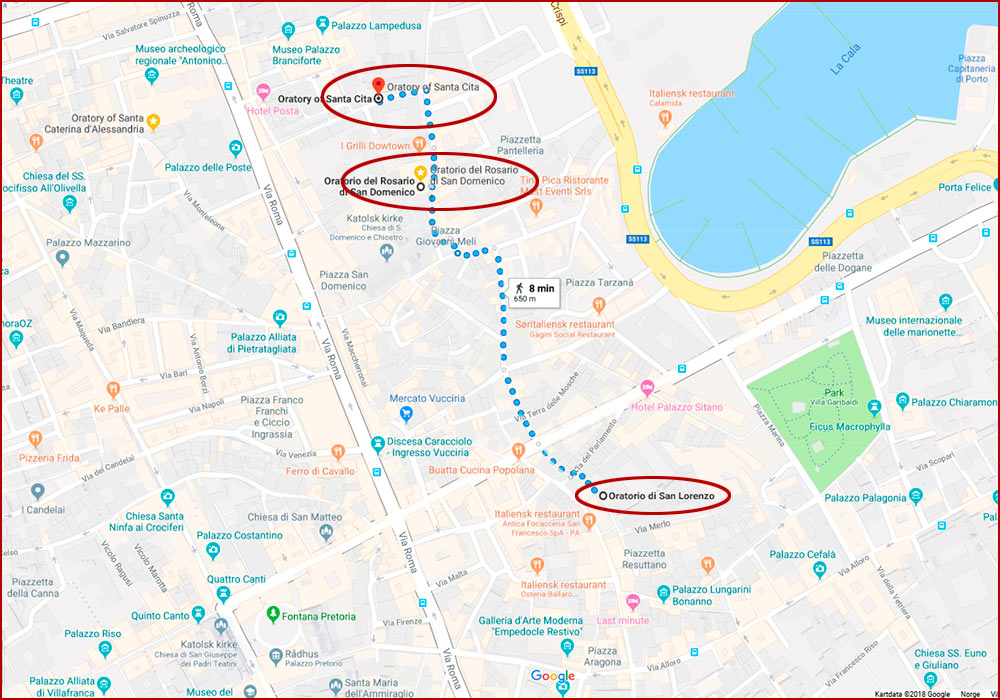

The Serpotta Oratories in Palermo

Oratorio of Santa Cita (1668–1718)

Oratorio of San Lorenzo (1690/98–1706)

Oratorio di San Domenico (1710–17)

Oratorio di Santa Caterina D’Alessandria

Oratorio di San Mercurio (1677–82)

The Serpotta workshop’s art is analyzed by Donald Garstang in Giacomo Serpotta and the Stuccatori of Palermo 1560–1790.

Source

Donald Garstang: Giacomo Serpotta and the Stuccatori of Palermo 1560-1790

Where to Find the Most Important Serpotta Oratorios in Palermo