The Romans in Sicily

Sicily, according to Cato, was "the nurse at whose breast the Roman people is fed". Sicily proved to be vital to Rome for a steady supply of grain.

In 264 Rome attacked the Carthaginian in what was to become the First Punic War (264-241 BC)

In 212 BC the last independent state Syracuse was defeated by the Romans

In the middle of the 5th century the Vandals started raiding the coastal towns of Sicily. About 50 years later they took control of the whole island. In 535 BC Sicily became part of the Byzantine empire.

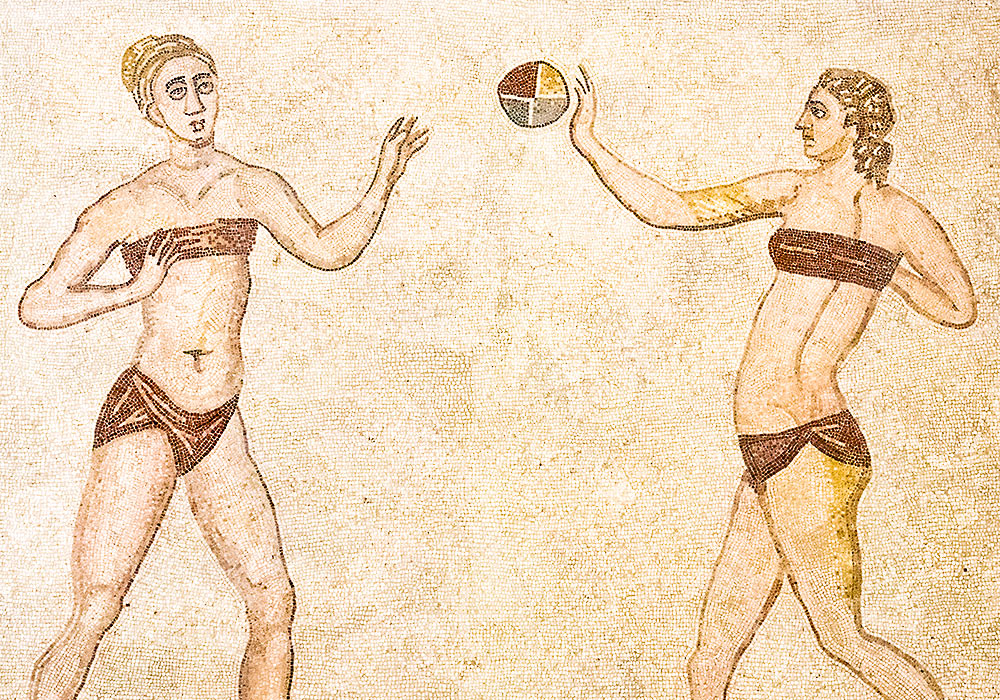

Mosaic floor in Villa Romana del Casale, Piazza Armerina.

Sicily was the first Roman province, acquired after the First Punic War with Carthage in 241 BC. Initially, only the western part of the island was under Roman control, but after the defeat of the Kingdom of Siracusa in 212 BC during the Second Punic War, all of Sicily, along with Malta and nearby islands, became part of the Roman Republic. Sicily was crucial to Rome as a primary source of grain, leading to heavy extraction and the First and Second Servile Wars in the second century BC.

In the first century BC, the governor Verres became infamous for corruption, prosecuted by Cicero. During Rome's civil wars, Sicily was controlled by Sextus Pompey but fell to Augustus in 36 BC, who reorganized the island and established Roman colonies.

Under Roman rule, Sicily was a peaceful, agrarian province with thriving cities like Siracusa, Catania, Lilybaeum, and Panormus (Palermo). The island's main languages were Greek and Latin, though Punic, Hebrew, and other languages were spoken. Jewish and Christian communities developed, especially after AD 200.

After the fall of the Western Roman Empire in 476, Sicily briefly came under Vandal control but returned to Roman rule under the Eastern Empire. It remained part of the Byzantine Empire until the 9th century.

Cicero on Sicily

“Of all foreign nations Sicily was the first who joined herself to the friendship and alliance of the Roman people. She was the first to be called a province; and the provinces are a great ornament to the empire. She was the first who taught our ancestors how glorious a thing it was to rule over foreign nations. She alone has displayed such good faith and such good will towards the Roman people, that the states of that island which have once come into our alliance have never revolted afterwards, but many of them, and those the most illustrious of them, have remained firm to our friendship for ever.”

Cicero, Marcus Tullius. Cicero: Against Verres in Latin + English (SPQR Study Guides Book 4) . Paul Hudson. Kindle Edition.

Siracusa

The Roman amphitheatre in Siracusa (140m by 119m). It was used by gladiator fights with wild beasts. The rectangular depression was probably for the machinery used in the spectacles.

Gladiatorial combat likely began as funeral rites during the Punic Wars (3rd century BC) and soon became central to Roman politics and entertainment. The games reached their height between the 1st century BC and 2nd century AD, featuring lavish spectacles. However, Christian disapproval and changing societal values led to the games’ decline in the 5th century.

The origins of gladiators and their games are debated. Nicolaus of Damascus (1st century BC) believed they were Etruscan, while Livy attributed their first appearance to the Campanians in 310 BC after a victory over the Samnites. Isidore of Seville (7th century AD) linked the word “lanista” (gladiator manager) and “Charon” (an arena official) to Etruscan roots.

Some modern scholars support a Campanian origin based on pictorial evidence, such as 4th-century BC Paestum frescoes showing fighters in funeral rites. Livy credits Rome’s first gladiator games in 264 BC to Decimus Junius Brutus, honoring his father. The games evolved through Rome’s conflicts with the Samnites, with the Samnite gladiator type becoming the most popular.

Gladiatorial games were extravagant tools for political self-promotion in Rome, offering free entertainment while bolstering the influence of their sponsors. Ambitious citizens might delay their munera (gladiator shows) until election season to win votes with lavish spectacles. Even those in power, like Sulla, famously broke sumptuary laws to host opulent games for his wife’s funeral.

Julius Caesar, during his aedileship in 65 BC, staged massive games with 320 gladiators in silver armor, despite immense personal debt. His lavish shows blurred the line between funerary rites and public entertainment, enhancing his popularity. Later, Augustus formalized the games as civic duties, imposing spending limits and restricting private munera. However, even emperors like Trajan, who used 10,000 gladiators and 11,000 animals to celebrate victories, saw costs spiral. Legislation to control spending, including by Marcus Aurelius, failed to curb the growing excesses of gladiatorial games.

The 3rd-century crisis strained the Roman Empire’s finances, making the obligatory gladiator games burdensome for magistrates, though emperors continued subsidizing them due to public demand. Christian writer Tertullian condemned the games, calling them spiritually harmful and a form of pagan sacrifice.

In 365, Emperor Valentinian I sought to limit expenses on gladiatorial games and prevent Christians from being sentenced to the arena. Theodosius I’s adoption of Nicene Christianity in 393 banned pagan festivals, and his successor, Honorius, officially ended the gladiator games in 399 and 404. Valentinian III reinforced the ban in 438. Interest in the games had already declined, though venationes (beast hunts) persisted. In the Byzantine Empire, theatrical shows and chariot races remained popular, with imperial support.

The earliest gladiator types were modeled after Rome's enemies: the Samnite, Thracian, and Gaul. As these enemies were absorbed into the empire, their gladiator names were changed—Samnite became the secutor and Gaul became the murmillo. Initially, gladiators of similar types fought one another, but by the late Republic, "fantasy" matchups emerged, pairing dissimilar fighters like the heavily armored secutor against the nimble, lightly-armored retiarius, armed with a net and trident.

Some gladiators fought from chariots or horseback, while others, like the cestus fighters from Greece, used lethal boxing gloves. The gladiator trade spanned the empire, fed by prisoners of war like Jewish captives after the Jewish Revolt. Training as a gladiator was seen as a chance for captured enemy soldiers to regain their honor through combat.

Gladiators also came from slaves condemned to the arena and paid volunteers (auctorati), who by the late Republic made up about half of all gladiators. For the poor and non-citizens, becoming a gladiator offered food, shelter, and a shot at wealth and fame. Gladiators kept their prize money and gifts; some, like Spiculus under Nero, gained wealth and property comparable to those of Roman generals.

The Best Gladiator Films

Gladiator (2000)

The Eagle (2011)

Ben-Hur (1959)

Spartacus (1960)

Centurion (2010)

Demetrius And The Gladiators (1954)

Barabbas (1961)

Halaesa

Statue of Ceres, in the Antiquarium at Halaesa on the north coast of Sicily, some 23 km from Cefalù. Ceres was the goddess of agriculture, grain crops, fertility and motherly relationships and patron of Sicily. Ceres, in Roman mythology, was equivalent to the Greek Demeter.

Roman mosaics

Mosaic on pavement from the Roman period, 2nd century BC. Information from Parco Archeologico di Naxos: "The pavement combines polychrome (yellow, pink, red, grey and black) cut and polished pebbles and relatively large polygonal black and white tesserae; the central geometric panes features a diamond shape inside a large square on which there is a six petaled flower om a black background. Four darting dolphins occupy the triangular shaped corners. The technique and the style date from 2nd century BC with parallels in Athens, Delos and Eretria."

If you are interested in Roman mosaics, the fantastic museum at Villa Romana del Casale, near Piazza Armerina, is the place to go.

The half-naked lovers in Villa Romana del Casale, Piazza Armerina. The woman's hair is pulled up and she has a Junoesque stature with wide hips, which, according to Giuseppe di Giovanni, shows the Ancient Roman's taste in women at the time. It gave women status to be overweight since it was a way to show off the wealth of the family, the importance of the husband and the prosperity of his business. The man is carrying a basket of fruit.

The "Bikini Girls" playing with a coloured ball. They are taking part in an Olympic pentathlon competition. Villa Romana del Casale, Piazza Armerina

Villa Romana del Casale, Piazza Armerina

Cupids fishing. Villa Romana del Casale, Piazza Armerina

Mosaic floor in Villa Romana del Casale, Piazza Armerina.

Villa Romana del Casale, Piazza Armerina

Villa Romana del Casale, Piazza Armerina

Villa Romana del Casale, Piazza Armerina

Villa Romana del Casale, Piazza Armerina

Mosaic floor in Villa Romana del Casale, Piazza Armerina.

Mosaic decoration in the childrens' room. Villa Romana del Casale, Piazza Armerina

Mosaic floor from via Cappuccini, Taormina. AD C2.

Ancient Rome (3D animation)

Speakers: Dr. Bernard Frischer and Dr. Steven Zucker

Art

Hercules wrestling with Antaeus. Marble support for table-top. Greek, 200-100 BC. Found off the coast of Catania. Ashmolean Museum / Museo Civico 'Castello Ursino', Catania. The cartibulum was used in grand Roman villas to display the family's silver plate.

Part of the exhibition Storms, War & Shipwrecks - Treasures from the Sicilian Seas at the Ashmolean Museum, June-September 2016.

Fragment of a life-size bronze elephant statue, 3rd century BC. Height: 63 cm. On the foot, a patina is visible, caused by the touch of countless hands. This suggests that the bronze elephant must have stood in a public place. According to Rossella Giglio, the technical and decorative characteristics point to a Phoenician-Sicilian, northern-African or Iberian origin - or a workshop in Rome. The foot was found in the Mediterranean Sea between Sicily and Tunisia on 3 July 1999 from the trawler Capitan Ciccio. (Sicily and the Sea, Allard Pierson Museum, 2015)

Detail of the bronze elephant foot found in the Mediterranean Sea between Sicily and Tunisia on 3 July 1999.

Click here for an interactive Roman Map

Articles

Romans Used to Ward Off Sickness with Flying Penis Amulets